Why Foreign Companies Fail at Import Compliance

7 Strategic Patterns for 2026

A strategic compliance framework covering IT, server, and high risk imports across key jurisdictions.

1. Introduction — The New Reality of Import Compliance

Global cross-border trade has shifted dramatically. Simple procedural compliance “fill the form,shipment arrives” is no longer sufficient in 2026 because customs authorities worldwide are integrating advanced digital systems, AI risk profiling, and synchronized tax enforcement frameworks into their regimes. What went unchecked a few years ago due to manual inspection limits is now systematically detected and flagged by automated systems. This isn’t a future threat it’s an active, ongoing transition that is reshaping import risk globally. This analysis reflects observed enforcement and audit exposure patterns, not third-party advisory opinions.

The Importer of Record (IOR) is legally accountable for customs compliance, duty and tax payment, and recordkeeping across jurisdictions. Failure to understand and manage these responsibilities exposes companies especially in high value sectors such as IT, servers, and network equipment to more frequent audits, deeper scrutiny, and heavier enforcement outcomes.

2. Evidence Anchor — 2026 Import Compliance Risk Matrix

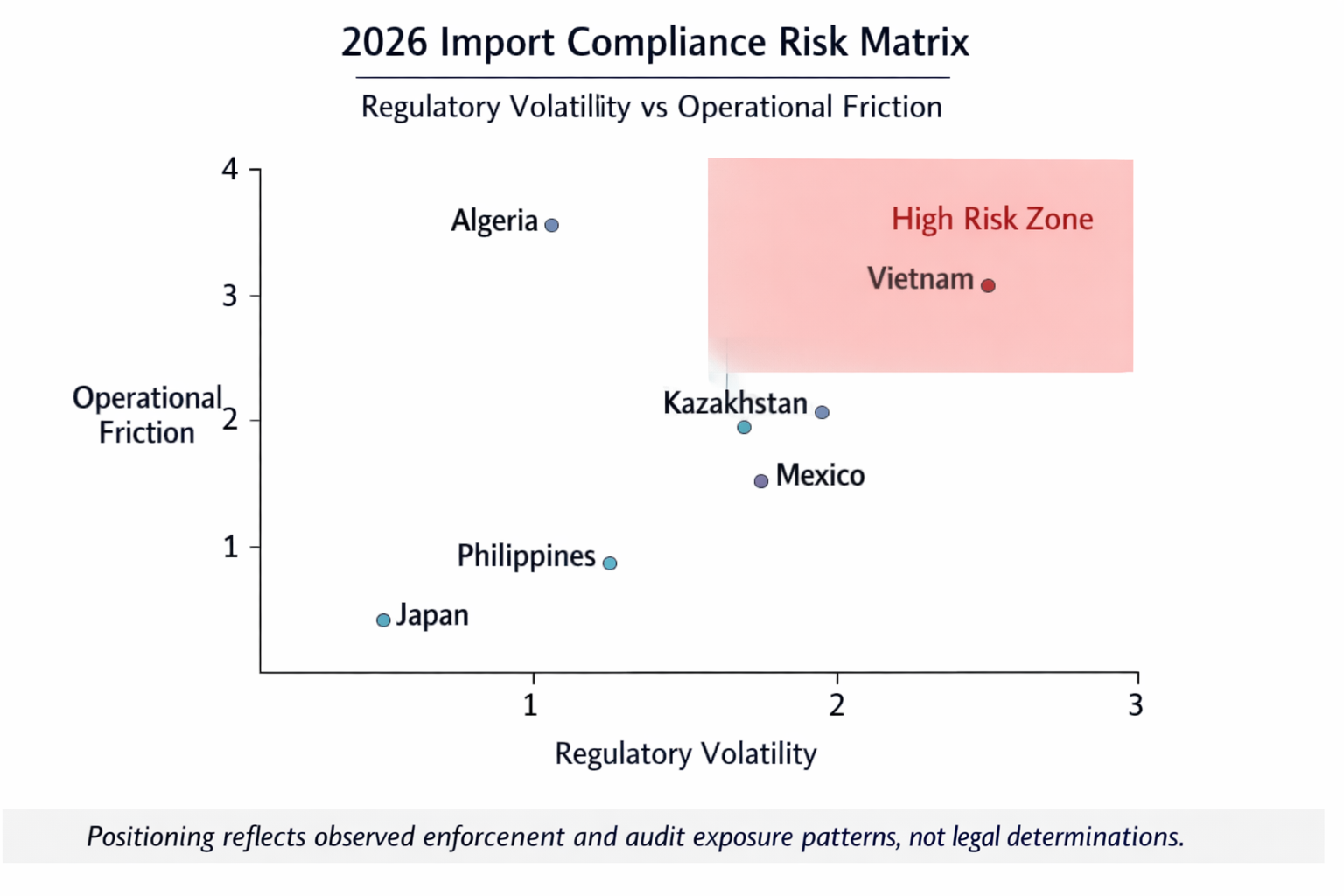

Visual: Regulatory Volatility vs Operational Friction

This simple quadrant graphic highlights where major markets stand in 2026 based on enforceability and procedural complexity:

| Country | Regulatory Volatility | Operational Friction | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnam | High (AI-linked compliance regime) | High (customs + documentation oversight) | Rapid digitalization of tax & customs procedures with tighter auditing mechanisms |

| Algeria | Medium | Very High (permits + cross-agency controls) | Complex bank & permit synchronization creates bottlenecks |

| Kazakhstan | High | Medium | Emerging Eurasian trade complexity & representative requirements |

| Mexico | Medium | High | Expanded HS code revisions & tariff risks ahead of trade reviews |

| Philippines | Medium | Medium | Documentation precision needed for clearance |

| Japan | Low | Low | Benchmarked transparency coupled with strict standards |

X = Regulatory Volatility (changes to law, AI integration, tax sync), Y = Operational Friction (customs complexity, permit bottlenecks).

This risk matrix is not just a graph it summarizes the new compliance landscape where some markets actively enforce and others retain legacy risk tolerance that is rapidly eroding.

3. The 7 Strategic Patterns of Non-Compliance in 2026

Each pattern below combines observed enforcement trends with high risk operational examples. These are not generic compliance checklists they are data validated failure archetypes matched with global trade conditions.

Pattern #1 — HS Code Drift (Vietnam, Philippines)

Modern enforcement regimes do more than check codes: they cross-verify classification against audit data, value-weight analytics, and historical records. A misclassified HS code on server or network imports often triggers a deeper audit cascade not just a tariff adjustment. Misclassification can lead to late payment penalties, forced re-valuation, and downstream tax reconciliation actions.

Audit teams use AI and data science to flag discrepancies across years of filings, making superficial classification enforcement a high risk trigger. This is particularly acute for IT, electronic, and telecom infrastructure equipment, where nuanced product descriptions and multi function products are common.

For detailed jurisdiction specific execution, see Vietnam IOR execution framework and Philippines IOR execution framework.

Pattern #2 — Permit Paralysis (Algeria, Kazakhstan)

In some high friction markets, the challenge isn’t obtaining a permit it’s synchronizing approvals across ministries, banks, and customs systems. Algeria’s model, for example, couples import permits with foreign exchange controls and banking compliance, creating a multi layer screening process that often stalls shipments more than classification or duty disputes.

This pattern accentuates when local officials integrate compliance systems across agencies these aren’t isolated checks but linked enforcement points, increasing the operational cost and delay risk.

For detailed jurisdiction specific execution, see Algeria IOR execution framework and Kazakhstan IOR execution framework.

Pattern #3 — Entity Substance Requirements (Mexico)

A recurring enforcement theme globally: customs and fiscal authorities are no longer satisfied with paper compliance. They evaluate whether the entity using the IOR structure has real operational substance economic activity, local financial presence, tax records, and commercial integration.

Nominal or purely “paper” IORs those created solely for compliance paperwork without depth of operational integration are increasingly flagged for further scrutiny over unrelated shipments. This isn’t speculation; it is a documented enforcement orientation across jurisdictions aiming to prevent regulatory arbitrage.

For detailed jurisdiction specific execution, see Mexico IOR execution framework.

Pattern #4 — Indirect Tax Exposure (Japan, Thailand, Mexico)

Non-direct tax exposure refers to situations where missteps in compliance trigger tax liabilities instead of or in addition to customs penalties. Even in lower risk countries like Japan, emerging VAT, digital tax reporting requirements, and post clearance tax scrutiny mean that a customs clearance mistake can induce broader tax exposure.

What once was perceived as a normal duty fee misstatement is now routinely escalated to financial reporting and tax alignment errors, significantly increasing total compliance cost.

For detailed jurisdiction specific execution, see Japan IOR execution framework.

Pattern #5 — The PoA Loop (Kazakhstan & Serbia)

Power of Attorney (PoA) arrangements indispensable in many IOR setups are now frequently examined not just for legitimacy but for operational control and accountability. In markets where trade frameworks leverage PoA for local representation, customs and legal audits increasingly evaluate whether the local agent truly executes compliance or if the principal retains effective control.

This pattern underscores the danger of outsourcing compliance without sufficient oversight mechanisms embedded in the IOR structure itself.

Pattern #6 — Real-Time Compliance Reporting Failures (Vietnam, Turkey, Mexico)

Many jurisdictions are deploying digital compliance gateways where customs documentation, invoicing systems, and tax reporting tools synchronize in real time. Even slight mismatches between invoice metadata and customs declaration fields can generate automated rejection codes, leading to extended inspections and triggered audits.

This is particularly pronounced for high value and serial-tracked equipment like servers and network hardware, where regulatory data points must align across platforms.

Pattern #7 — Structural Local Dependency Risk (Malaysia example)

Relying on a single dependent local partner whether for physical presence, local bank access, or customs facilitation introduces a single point of failure that global compliance regimes can exploit. Structural dependency is less about a single mistake and more about fragile compliance continuity in automated control environments.

For detailed jurisdiction specific execution, see Malaysia IOR execution framework.

4. Observed Enforcement Shift: The Era of Data Driven Audits

Across emerging and developed markets alike, customs authorities are integrating audit tools, intelligence sharing platforms, and machine learning risk scorers to monitor imports more dynamically. Vietnam’s recent customs regulatory changes include expanded import and export procedures with post clearance audit mechanisms designed to support closer scrutiny of high value, tech-linked trade flows. Emerging market intelligence data also shows that inconsistent customs licensing regimes, currency payment volatility, and rules that were previously vague are now tightly enforced, increasing audit risk across multiple import categories. This transition fundamentally changes how risks are surfaced compliance is no longer periodic, it is continuous and automated.

For a broader analysis of global customs compliance trends, see our Global IOR & Customs Compliance Outlook 2026.

5. Strategic Mitigation Framework — Turning Risk into Control

The seven non-compliance patterns outlined above are not isolated operational failures. They represent structural weaknesses in how import compliance is designed, monitored, and executed. Addressing them requires a shift away from reactive correction models toward a framework-first control architecture.

In 2026, effective import compliance strategies increasingly rely on the following integrated control layers:

- Pre-classification AI validation: Automated HS code and valuation checks performed before shipment execution to identify classification drift and historical inconsistencies.

- End-to-end documentation traceability: Unified tracking of invoices, permits, customs declarations, and tax filings across systems to prevent data divergence during audits.

- Entity operational substance verification: Continuous validation that the Importer of Record maintains real economic presence, financial activity, and procedural control within the jurisdiction.

- Live tax and customs synchronization: Alignment of customs filings with indirect tax, e-invoicing, and post-clearance reporting platforms to reduce automated rejection and escalation triggers.

- Cross-agency permit mapping: Pre-clearance modeling of approvals involving customs, sector regulators, banking controls, and foreign exchange authorities.

- Red-teaming of Power of Attorney structures: Stress-testing PoA arrangements to identify accountability gaps, control leakage, and audit exposure before enforcement scrutiny occurs.

These measures do not eliminate enforcement risk. They reduce audit triggers by ensuring that compliance failures are detected and corrected internally before they surface through automated government systems.

6. Conclusion & Actionable Roadmap

The global transition from tolerance-based oversight to technology-driven enforcement is already underway. For companies importing IT equipment, servers, network infrastructure, and other high-value goods, compliance has become a continuous verification process rather than a procedural formality.

Traditional paper-based Importer of Record models that lack operational substance, data integrity, and system-level coordination are increasingly exposed under modern scrutiny. In an environment shaped by AI risk profiling and cross-agency data synchronization, reactive compliance approaches are structurally disadvantaged.

Organizations that adapt successfully in 2026 follow a different trajectory:

- They design compliance as a control framework, not a checklist.

- They validate risk before shipment execution, not after audit initiation.

- They align legal responsibility with operational reality.

The choice is no longer between compliance and non-compliance. It is between framework-led readiness and repeated cycles of audits, penalties, and clearance disruption. In the current enforcement landscape, readiness determines resilience.

Unless otherwise stated, all regulatory references and enforcement trends cited in this report reflect laws, directives, and administrative measures that have been formally enacted, officially published, or publicly announced with officially confirmed implementation timelines as of Q1 2026. Where applicable, references include regulations entering force, undergoing phased enforcement, or subject to binding administrative guidance within the 2025–2026 cycle.

Regulatory & Enforcement References (Technical Evidence Layer)

The following primary sources and official directives form the regulatory basis for the trends and risk projections analyzed in this report.

- Vietnam: Law on Digital Technology Industry (No. 71/2025/QH15) – Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC)

- Mexico: Ley de los Impuestos Generales de Importación y Exportación (TIGIE) – 2026 Revision – Servicio de Administración Tributaria (SAT)

- Singapore: GST InvoiceNow Requirement (Peppol Mandate) – Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS)

- Philippines: Customs Administrative Order (CAO) No. 01-2019 (enhanced PCA analytics 2025–2026) – Bureau of Customs (BOC)

- Turkey: TAREKS (Risk-Based Control System) & BTK Technical Compliance Directives – Ministry of Trade / Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK)